So many women writers seem to be dying lately, over the last few years especially. Is it because I’m a woman writer that I happen take more notice, or is it just that I have been influenced and formed so strongly by their presence as literary mothers in my head and heart? I’m not sure, to be honest. I just know that my heart sinks when I hear that another woman has gone on. I dig through my bookshelves and revisit their work, feeling comforted by their voices telling me stories in my head. I did this with Maya Angelou and Mary Oliver’s writing after their deaths, reviewing the depth and breadth of their work. The poets always get to me when they go, whether men or women, and I feel as if someone has yanked my heart out of my chest and shoved it back in again, all tattered and worn. I always cry. Always.

Joan Didion was someone I never thought would die. You likely know how that happens inside your head, especially if you’re a writer? There is always a sense of shock and denial that comes from hearing of a writer’s passing, even when you’ve never seen them read in person, but have only ever huddled down with their books on a rainy night. Perhaps it was that I first read Didion—in earnest and not just in passing—after the death of my own mother in December 2008. I was in the middle of a major depressive episode then. Someone, either another woman writer, or maybe even my therapist, suggested that I read The Year of Magical Thinking (2005). I scoffed, thinking ‘It’s just another book about grief and loss, like all of the others I’ve tried, so what good will it do me?’ Thankfully, I disregarded that subversive inside voice and went off to buy a copy of the book.

I often think that stigma swirls around those of us who have lived with and survived mental illness. The other sort of stigma that I’ve noticed in the last fourteen years of my life has to do with death. The western world really doesn’t seem to want to engage in what deep and intense loss can do to a person’s psyche and their way of being in the world afterwards. Death—and grieving—is so sterile and hygienic now that it’s not as naturally woven into our society as it once was. I remember my great aunts telling me, when I was a teenager, that my great-grandfather, James Cornelius Kelly, was given a proper Irish wake in the sunroom of their big red brick house here in Sudbury. They may very well have told me that while I was sitting on the couch in that very same sunroom, looking out the window towards the big back yard with the willow tree, wondering where they would have put the casket in that tiny room with big windows. Would it have been where the couch was now? My great-grandfather died in 1950. Then, death was part of life, and grieving was seen as part of living, too. The act of grieving a loss deeply wasn’t something that was stigmatized or rushed through without too much thought. Now, it’s pinned to a calendar with a certain number of days given away from work, not caring that your heart might take longer to recover from such a final parting of ways.

Reading Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking—when I was most missing my mother after she died—I found a voice that sounded so much like the one in my head. When Didion died in December 2021, I wept. She had been with me after my mother’s death, you see, and that meant something to me. I re-read both The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights (2011) in January and found myself transfixed yet again by the Netflix documentary Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold. She knew what grief was about, losing her husband and then her daughter. She knew the pain and intensity of that kind of loss. It’s strange, but when you’ve had a great deal of loss in your life, you fear people disappearing—because they always will—but yet you also feel drawn to others who have had to go through difficult times in life. They will not have rushed through the grieving, you think, and so will have let it change them from the inside out in a deeper way, for the better.

When I first read it, years ago, I underlined the passages that most spoke to me in The Year of Magical Thinking: “Grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it. We anticipate (we know) that someone close to us could die, but we do not look beyond the few days or weeks that immediately follow such an imagined death. We might expect if the death is sudden to feel shock. We do not expect this shock to be obliterative, dislocating to both body and mind.” Yes. Death can be obliterative. It will fracture a life and then you’ll be left to rebuild it, to make it stronger somehow.

At the very end of The Year of Magical Thinking, I circled and starred some lines that made me cry. The first was “I look for resolution and find none” and the second was “I know why we try to keep the dead alive: we try to keep them alive in order to keep them with us.” Ah, I remember thinking—and I still do now, on a dull grey February day in Northern Ontario—the pain of when people go, when they disappear, will always be something that comes without closure. All you can do, when people go, is to know there isn’t such a thing as closure. It’s a fierce and false myth. Joan Didion taught me that through her writing, and it is a lesson for which I will always be most grateful because it’s one that needs to be taken in, to almost be consumed and integrated.

There’s a song by Craig Cardiff that I often listen to when I think of the people I’ve lost. It’s called “When People Go.” So many have disappeared from my life. Some go when they die, and others disappear when their paths diverge from mine. Either way, the grief is still as deep when someone departs from your life, a hole that can’t be filled afterwards. In his song, Cardiff sings plaintively: “When people go, when people leave, makes some people cry, makes some people drink…it’s the saddest thing.” I love the acoustic version that I found on YouTube a few years ago, mostly because the words are so painfully true. The song—his words and voice—makes me think of Joan Didion, who wasn’t afraid to embrace the deep pain of loss. The people who have gone are ones who are like boats at sea, never to come back.

What I love about Joan Didion’s writing on grief—which feels like poetry to me most days when I read her memoirs—is that she didn’t avoid the pain of it all as so many try to do. She sat with it, wondering what to do with her husband John Gregory Dunne’s clothing and shoes after he died. Best not to give away his shoes in case he happened to return. In Blue Nights, too, a book that speaks to the death of her daughter, Quintana, Didion further explores illness, aging, and death. All of these things dance with grief, as we come to grips with the fact that we are—indeed—more mortal than we’d ever like to admit.

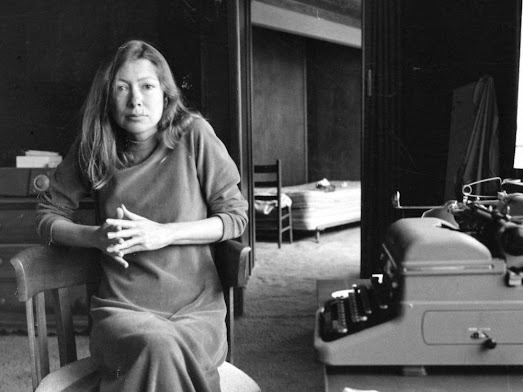

I think of Joan Didion quite often these days. When I miss her being on the planet, I think of the raw and genuine truths found in The Year of Magical Thinking. I revisit her face and her voice as she speaks of the rich beauty of her life in that brilliant documentary—her hands rising like birds as she speaks, and then falling to rest in her lap. Grief is like that, rising and falling, and then resting in your heart and memory. She taught me that through her writing and I’ll be forever grateful to her for that gift.

Kim Fahner lives and writes in Sudbury, Ontario. She

was poet laureate in Sudbury from 2016-18, and was the first woman appointed to

the role. Kim's latest book of poems is These Wings (Pedlar Press, 2019). She's

a member of the League of Canadian Poets, the Ontario representative of The

Writers' Union of Canada (2020-22), and a supporting member of the Playwrights

Guild of Canada. Kim can be reached via her author website at www.kimfahner.com

No comments:

Post a Comment