Dale Spender: Looking Behind, Looking Ahead

Somebody

pointed it out to me—somebody on the internet, of course—that hardly any of the

books I’d studied in English class were written by women. Women writers were

infrequently mentioned when I read books about books too. With one

exception: I understood that women’s writing, such as it was, began with Jane

Austen.

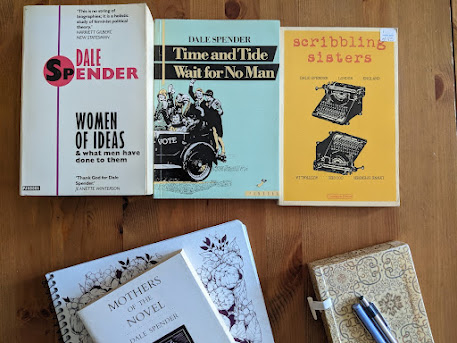

Then—I learned that Jane Austen had a past, via Dale Spender’s Mothers of the Novel: 100 Good Women Writers before Jane Austen (1986). Suddenly I recognized that Jane Austen might have believed that a woman could write novels because she had read other novels by women. Those early women writers’ books—they were her internet: information that illuminates possibility.

Born in 1943 in Australia, Dale Spender started lecturing at James Cook University in 1974, before moving to London and publishing Man Made Language (1980). "Language,” she writes, “helps form the limits of our reality. It is our means of ordering, classifying and manipulating the world.” When I discovered her work, I was just beginning to understand relationships between language and society, beginning to assess complex systems that protect existing power structures, still sussing out the potential to disrupt.

Language and story shaped my understanding; Spender’s work broadened it. She writes about a similar sense of expansion in 1982’s Women of Ideas. In her formal studies, she became aware of the suffragettes, but learned much later that in 1911, there had been twenty-one regular feminist periodicals in Britain, a feminist book shop and press, and a bank administered by and dedicated to women. And not only was the early-20th-century women’s movement “bigger, stronger and more influential” than she had previously understood, but “it might not have been the only such movement.”

Spender glances backward to Mary Beard’s Woman as Force in 1946 and she imagines Beard looking back to Woolf in 1928 with A Room of One’s Own, and Woolf looking back to Matilda Joslyn Gage and Margaret Fuller. If “every generation must begin virtually at the beginning and start again to forge the meanings of women’s existence in a patriarchal world,” existing power structures maintain power.

This unravelling can be disrupted with knowledge, however, as Spender explains, in her foreword to Feminist Theorists: Three Centuries of Key Women Thinkers (1983): “This then is a glimpse of some of women’s intellectual traditions over the last three centuries. It is a glimpse however, which patriarchy would prefer us to do without. We can see that what we are doing today is not something new but something old: this is a source of strength and power.”

European women comprise the bulk of Women of Ideas’ 800 pages, but in the couple hundred pages dedicated to North Americans, Spender discusses Ida B. Wells, Sojourner Truth, and Josephine Ruffin. In particular, she considers Josephine Ruffin’s speech to a group of women in 1895 Boston, which alluded to an earlier era when white and Black women were united in suffrage work. Just decades later, in Ruffin’s time, women once acting in concert were now in conflict.

Just a few weeks ago, a New York Times Book Review reader notes in a letter to the editor that Honorée Jeffers’s review of Toni Morrison’s Recitatif draws attention to Morrison’s accomplishments and significance but overlooks her literary debt to James Baldwin. It’s another reminder: how quickly we take those our ancestors for granted.

But where does it end, this backwards glance? Must a present-day writer include a bibliography as long as Dale Spender’s in Women of Ideas to acknowledge even some of their predecessors? I’ve read enough now to be able to glimpse just how much is missing—even still—in her eight hundred pages.

Perhaps a better question is, will we begin? Rereading Dale Spender this year has reminded me how readily we overlook the potential that resided in the past. Spender’s work establishing the Pandora Press imprint in Australia brought earlier women writers into my stacks, as did the Virago Modern Classics imprint: narratives that remind contemporary readers that yesterday’s readers also dared and dreamed.

If there is strength and power in recognizing a heritage of resistance and insistence—looking back from Toni Morrison to James Baldwin (Zora Neale Hurston, Ann Petry, and Paule Marshall too), from Josephine Ruffin to Hannah Crafts—reading backlists could transform an ordinary reader into a revolutionary. Through rereading and rediscovering, we illuminate the possibilities both behind and ahead of us, so we might sustain rather than rebuild.

Marcie McCauley reads, writes, and lives in Toronto (which was built on the homelands of Indigenous peoples – including the Haudenosaunee, Anishnaabeg and the Wendat – land still inhabited by their descendants). Her writing has been published in American, British and Canadian magazines and journals, in print and online.

No comments:

Post a Comment